Traditionally ATV and its associated analog 7 MHz bandwidth has been restricted to UHF and microwave bands, and bandplans have reflected that. With the global emergence of DATV and RBTV (reduced bandwidth TV) experimentation is now taking place on lower bands, down as far as 10m.

During a recent radio club meeting where there was general discussion about the new fee-less class licence system just introduced in VK (it began on 19 February 2024), I was looking at the pages on the ACMA website (the regulator in VK) and followed links to the legislation (Radiocommunications (Amateur Stations) Class Licence 2023), a relatively succinct 34 pages complement to the 483pp of Radiocommunications Act 1992.

Alongside conditions about qualifications, licences, callsigns and electromagnetic energy exposure, there is a schedule detailing “Permitted frequencies and limits on operation” organised in terms of licence type – Foundation, Standard or Advanced.

The main national organisation of Australian radio amateurs, the Wireless Institute of Australia last updated its detailed 32 page bandplan in September 2020.

In contrast the recent handful of pages listing permitted frequencies and limitations indicates a light touch administration that may well enable innovation on the bands especially above 28 MHz and future proof the management of these bands. (But of course legislation and band plans are different documents with different purposes.)

Above 52 MHz there are no bandwidth limitations on amateur transmissions.

The limitation imposed on transmissions on 10 m is

| If a person operates an amateur station with an emission mode that has a necessary bandwidth exceeding 16 kHz, the maximum power spectral density from the station must not be greater than 1 watt per 100 kHz |

Radiocommunications (Amateur Stations) Class Licence 2023

And the limitation on the 50-52 MHz segment of 6 m is

| A person must not operate an amateur station with an emission mode that has a necessary bandwidth exceeding 100 kHz |

Radiocommunications (Amateur Stations) Class Licence 2023

It will be interesting to see how different groups of amateur users negotiate a coordinated way to use the bands, and still maintain freedom for technical innovation for such modes as RBTV and DATV and whatever else might emerge in the future.

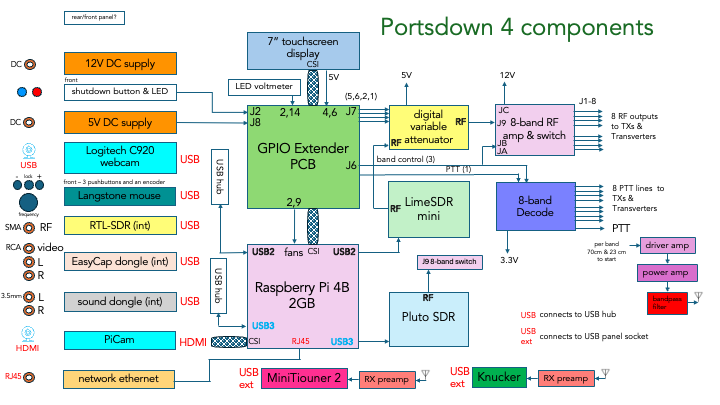

I imagine anyone building a Portsdown DATV setup in Australia like I am right now, should consider bands beyond 70 cm & 23 cm. Exciting times.