On Wednesday evening I went along to a talk at a nearby library by David Dufty about his recent book ‘The Secret Code-Breakers of Central Bureau – How Australia’s signals intelligence network helped win the Pacific War’ published last year by Scribe.

It’s a great story that does uncover previously unacknowledged contributions. Dufty’s interest was sparked by a newspaper mention of Australian wartime code-breaking on Anzac Day 2012. His interest triggered a comprehensive research trail.

It’s a great read with a solid bibliography. He interviewed about twenty people who worked on breaking the Japanese codes. From a standing start, the operation grew to involve over 4,300 Australians – a venture, Dufty says, it’s hard to imagine us being able to mount as readily today.

He mentioned many of the characters from Australia’s early radio history, including Mrs Mac, Florence MacKenzie, who trained thousands of women morse operators who in turn were used to train many Australian servicemen.

He also mentioned Eric Nave who was responsible for breaking Japan’s Naval codes. Nave as a young naval cadet had spent years in Japan learning the language and culture of the country.

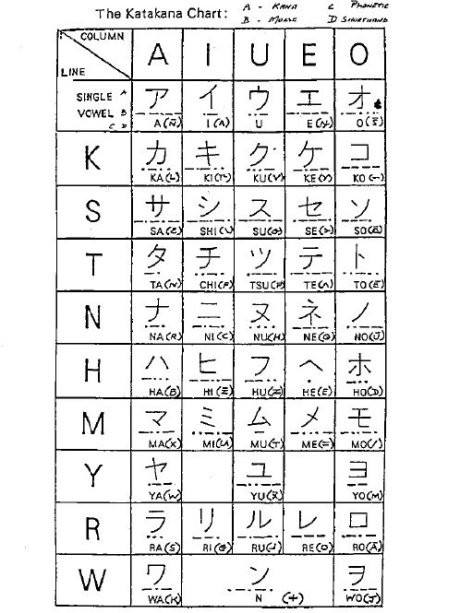

The character with the best nickname would have to be Keith ‘Zero’ Falconer. He was the country’s top interceptor of Japanese Kana coded messages. He got the nickname from his colleagues as every single day of Kana code training in Melbourne he would score zero errors in the test. Japanese hams can still be heard conversing in this code on the bands today.

The character who stands out from David Dufty’s talk on Wednesday evening is Stan or Pappy Clark. Apparently, prior to enlistment, his work was scripting radio serials for children. The mention of the magic word radio was enough to catch the eye of people recruiting for radio intelligence work, and it turned out to be a fortunate selection for Australia.

Stan Clark used his talents to develop a comprehensive knowledge of the Japanese communication networks and was able to analyse the dynamic ebb and flow of their radio traffic. Even if we weren’t able to decode every message the broad overview – which Dufty interpreted as the ‘metadata’ of the enemy’s radio communication – of this traffic analysis played a crucial role in determining the allied strategy of the war and effectively saved thousands of allied and enemy lives. Macarthur’s famous island hopping strategy was directly informed by this intelligence. One of the special things about Wednesday night was that unknown to Dufty until the end of his talk, Clark’s grandson and family were in the audience.